Finding and retaining top talent is an everlasting problem all start-ups must go through. Not only do start-ups have to compete with big name companies over excellent employees but start-ups also must realize that employees of the highest caliber usually plan to venture off on their own and start their own thing. To keep the employees for as long as possible, countless ideas have been proposed, including equity compensation; the basic idea behind is to give an employee a part of the company. As a partial owner, the employee is bound to care more about the success of the company as well as stay longer to make it happen. The most popular form of aligning the employee’s interests with that of the company is to give employees stock options.

This article will discuss employee equity compensation, starting from the very basic and going through everything you need to know. It will mostly focus on the whole process from the founder’s/ CEO’s perspective, but the article will also tackle how options affect employees.

What are options?

To make matters feel more concrete, let’s work with an example first, after which I’ll explain things in more detail:

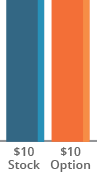

Let’s assume that the stock of company X is being traded today for 10 dollars. If you buy 10 shares of company X at 10 dollars a share, it would cost you 100 dollars. However, you can buy an option that allows you to purchase the same 10 stocks from the same company, company X, at the same price of 10 dollars per share any time you want during the next 10 years.

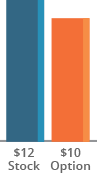

So, why buy the options instead of the stocks right away? For one, options are always significantly cheaper than the stocks they represent. Moreover, if the stock of company X rises in price over the next ten years and becomes 12 dollars, you can exercise your option, which is another way of saying that you’ll use the option to buy the stocks at the lower price of 10 dollars, and make a profit off of the difference between the current price (also known as fair market value or FMV, which is 12 dollars) and the price when you first bought the options (also known as strike price, which is 10 dollars).

On the other hand, if the stock price were to fall to 8 dollars, you won’t incur any losses beyond the original price of the options, unlike someone who bought the stocks back when they were worth 10 dollars a share. In this scenario, you wouldn’t have to exercise your options, and you might as well throw these options in the trash.

Having gone through the example, let’s look at things more formally:

Options are contractual obligations that allow the holder to purchase a certain stock at a predetermined price. Usually the price is set based on the date of issuance of the option, which is another way of saying that the predetermined price tends to be the stock price when the option is first issued. However, options aren’t valid indefinitely; they have an expiration date, or what is known as an exercise period. If the option isn’t used during that exercise period, it becomes void and null. Options are primarily used for hedging risk plus facilitating trades.

But still, why use options instead of shares?

A very simple question to ask at this stage is why stock options should be used instead of just giving the employees shares. After all, hedging risk and facilitating trades is all good and well when you are working in the stock market, but how does it apply to compensating employees working at a company?

The primary reason behind preferring options to direct shares is tax related: receiving direct shares is taxable, which might put an unnecessary financial strain on the employee. Contrarily, options are not taxable until they are exercised, if they are ever exercised. This gives the employee more control and doesn’t make the compensation financially burdening.

What kind of options are there?

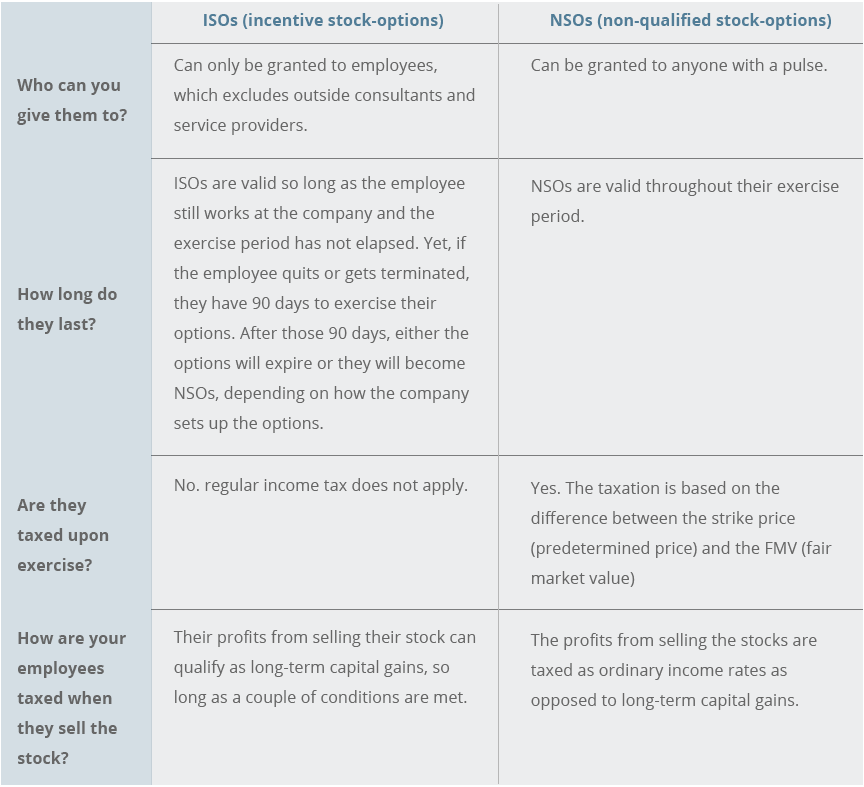

There are other forms of employee compensation besides options including phantom stocks, profits interest, and restricted stock. However, throughout this article we will be mainly focusing on two types of options: ISOs (which stands for Incentive stock-options) and NSOs (Non-qualified stock-options).

The main difference between ISOs and NSOs resides in how the tax man treats them. Nevertheless, here is a table that summarizes most of what you need to know:

In the above table, I mentioned that ISOs can qualify for long-term capital gains if a couple of conditions are satisfied. Before I delve into these conditions, I want to point out that long-term capital gains are a significant reduction in the rates of taxation of profits from selling shares. This reduction can be as much as 20%; an employee making a profit from selling stocks can be taxed 35%, which we’ll assume is his income rate, or the same employee can be taxed 15%, which is the long-term capital gains rate. As a result, understanding how to have the earnings classified as long-term gains is invaluable information for any employee. The conditions are as follows:

(1) The option must be exercised while the employee is still working for the company.

(2) Any and all shares issued when the option was exercised must not be sold for

(A) At least 1 year after the exercise of the option.

(B) At least 2 years after receiving the option.

A common problem faced by several employees is their lack of knowledge of these caveats, which leads to the employees being taxed at a much higher rate than necessary.

So how do you give your employees options?

The first thing you need to realize is that, unlike monetary compensation, giving away a part of the company is a decision that happens at the board level; a senior executive usually does not have the authority to make these decisions unilaterally. With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at the process of granting employees options.

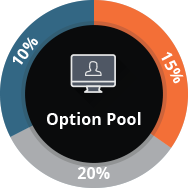

The first step is for the board to create an option pool, which becomes the main source for options granted to employees. The amount of stock designated to this option pool can range from 10% to 20% of the total number of outstanding shares of the company. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that the larger the pool the more likely that this pool will sustain the company during future grants. Furthermore, the size of the option pool will later factor on in the valuation of your company.

Once the pool is decided upon, each employee is granted a specific amount of stock options; the percentage of options you should grant your employees will be discussed later down the road. The number of shares each employee is entitled to is decided upon at the beginning of the employee’s contract, along with their salary. However, companies rarely, if ever, give an employee all their options right at the outset. Instead, the employees are put on a vesting schedule.

There are two primary types of vesting schedules:

- Performance based, where the employee receives a specific number of options after reaching a certain benchmark.

- Time based, where the employee receives a specific number of options after spending a certain amount of time at the company.

When it comes to time-based vesting schedules, companies implement a one-year cliff in the beginning often. A one-year cliff is another way of saying that a company withholds all options from an employee during that employee’s first year at the job. Upon completing their first year, employees receive twelve months’ worth of options, which is the same amount they would have received had the monthly vesting schedule started from the very first day of employment. The one-year cliff is done to incentivize employees to stay longer than a year.

The norm was for companies to put employees on a monthly vesting schedule that lasted four years with a one-year cliff at the beginning. Once the four years were over, the employee was up for a “refresher grant”, which is basically another set of options in order to keep the employee on longer.

Nowadays, things are currently changing: vesting periods are becoming longer and back loaded. Basically, what this means is that an employee receives a larger portion of the company over 5 or 6 years instead of 4. Moreover, when a company back loads the vesting period, it is giving the employee a larger percent of their options the more they stay at the company. For example, a four year back loaded vesting schedule might give an employee 10% of their shares after the first year of employment, 20% after the second year, 30% after the third, and 40% after the fourth.

Interestingly enough, there are specific situations in which an employee’s unvested options might be accelerated. These primarily arise when both the company is being sold and the employee is terminated; they are known as a double trigger acceleration, and they need to be approved by the board.

After receiving the options, the employee has the duration of the exercise period to make use of the options. Should the employee, for any reason, fail to capitalize on his grant, the options are forfeited and returned to the option pool.

Unless in the form of refresher grants, giving an employee extra options are a rarity. The only exception is when the employee gets promoted; promoted employees are given more grants to reflect the appropriate compensation for their new position.

When it comes time for an employee to sell their shares, companies tend to give themselves the right of first refusal. In more layman terms, companies buy from their employees the stocks at the current fair market value. This clause is carried out in order to prevent outsiders from owning shares of the company, especially if the company hasn’t gone public yet.

How much equity should you give your employees?

This is a tricky subject that straddles the line between art and science, and we need to agree to a few things before we can delve into the matter any further.

To start with, you need to realize that every employee working for your start-up is investing in both you and your start-up, just as much as a venture capitalist might actually put up a cash investment. After all, most of your employees are probably taking pay cuts to work at your company. That lost opportunity on its own is a form of investment. In addition, your employees, especially your early employees, will always contribute more to your company’s vision than any outside investor ever could. Moreover, the earlier an employee starts working for you, the more risk they shoulder. Hence, you should take all of this into consideration when thinking about compensating your employees.

There are countless models for distributing options. Nevertheless, we will look at one of the simpler ones:

- The following formula was proposed by Paul Graham: i=1/(1-n), where i is the average outcome of the company with the addition of a new individual and n is the worth of that new individual. Another way of interpreting this formula is n=(i-1)/i. For an excellent illustrative example on how to use this formula, follow this link. Problems with this formula lie in the fact that it is very difficult to define the amount of contribution an employee brings to a company.

- Another algorithm is to divide your employees into early hires and late hires. For early hires, you will usually have to give away full percentage points, 5% or 10% for example. For late hires, on the other hand, you need to develop further brackets depending on the amount of contribution to your company. For example, engineers contribute more than secretaries, so each one will belong in a different bracket. Now, for each bracket create a multiplier (M). Finally, for each individual employee, use this formula: Amount of shares= (current salary*total number of outstanding shares for company/ valuation of company)* multiplier (M). For more information on this formula, follow this link.

What about your employees? Do they always prefer options?

With the basics well behind us, it’s worth knowing what problems your employees might face with their options:

- One of the biggest problems facing employees with options is their inability to purchase the stocks, even at the strike price. This usually creates a bind for employees and traps them in a company, especially if the employees are concerned about losing the ISOs.

- Depending on the liquidation preferences of your investors (which is a pecking order of who gets paid what in the event of selling the company), these options might end up worth nothing.

- Employees need to wait for the options to vest, which represents a time investment on the employees’ part.

- Employees must contend with dilution issues when the company issues new shares. The best analogy to this is saying that you’ll give an employee 2 slices from a pie. However, instead of cutting the pie up into 10 slices, you’re going to cut it up into 20.

A couple of tips for the founders out there:

- You should realize that options are meant to be an incentive, but they shouldn’t be the primary lure you use. After all, there is a very real probability that your company might tank, and these options will become worthless. Plus, making the options your sole focus will automatically attract the wrong caliber of employees. Instead, focus on learning opportunities and room for growth. Options should be a bonus.

- Your employees deserve complete honesty. Therefore, be as transparent as possible with them. If they have any questions about their options or the worth of said options, be forthcoming with that information. Additionally, you should make the number of outstanding shares and the valuation of the company accessible information to all your employees.3. An important proviso is to abstain from making the options too complicated or too intricate. You don’t want your employees wasting time trying to figure out how much their options are worth rather than concentrating on the job at hand.

- An important proviso is to abstain from making the options too complicated or too intricate. You don’t want your employees wasting time trying to figure out how much their options are worth rather than concentrating on the job at hand.

Let’s talk

Schedule an intro call to learn about why MeldVal is important for your business. Or have any questions? We’re here to help.

Contact us